Our History

There has always been a dwelling on the site where Scale Hill now stands. The building as we now know it was constructed in the 1600s and it has provided hospitality and shelter to travellers for over 400 years.

Scale Hill was extended at the turn of the 1800s but it remains at large, both inside and out, as a 17th Century Coaching Inn, affording all who visit a comfortable and impressive base in the most unspoilt valley in the English Lake District.

For over 400 years Scale Hill has stood at the head of Crummock Water; she has survived Plague, The English Reformation, Revolution, The English Civil War (1642-1651), the Glorious Revolution of 1688, seen over 55 Prime Ministers in Office, 21 Monarchs on the Throne, survived through Two World Wars, the Spanish Flu, and now, the Covid-19 Pandemic.

In the course of its existence Scale Hill has welcomed many outstanding figures in the history of Art, Literature and Science: writers such as William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Harriet Martineau and Arthur Ransome; musicians and entertainers such as Paul Robeson, Donald Sutherland, William Arthur Poucher, and Joyce Grenfell; Political Thinkers such as William Wilberforce and Philip Noel-Baker, amongst many others, who all live on and visit to this day.

Today, Scale Hill is owned by Heather Thompson, who is the third generation of her family to run Scale Hill. Heather has a passion for local history and it is thanks to her that we know so much about Scale Hill and the people who have lived and worked, and visited Scale Hill before us. Along with her grown-up children, Megan, Derwent and Hayden, Heather is looking forward to welcoming you to the the next generation at Scale Hill.

Scale Hill, Loweswater c.1700s

Scale Hill, Loweswater c.1900s

Around 1400, the site upon which Scale Hill Hotel now stands was used by the people of Brackenthwaite, who lived in a collection of farmstead buildings, to manage their stock on the summer pasture, Brackenthwaite Hows.

Wills and inventorties show that the Robinson family were living at Scale Hill in the late 1600s. At this time, the property is owned by a Mr Robert Fisher of Hollings, who had other estates in Brackenthwaite, including Scale Hill. When he died he left his estate to his second eldest son, John Fisher (1643-1700) who had left Cumberland as a young man and had settled in Low Layton (Leyton), Essex, where he became a successful merchant. When the second son, John, died in 1700 he left an estate of some £50,000 (about £15 million in today’s money) including the property in Brackenthwaite and elsewhere in Cumberland.

John was the second son and unusually, he had inherited his fathers estate, rather than his older brother, Robert. During his liftetime, John made provision in his will for Robert’s Children, leaving them ‘all my estate, with the sheep and their heirs, at Brackenthwaite, Longthwaite, Fletcher’s and Scale-Hill, with Low Holmes and the Lake Crummock (fishing rights).’ However, John Fisher’s will was unsigned, unsealed and complex.

John’s son, John Fisher of Low Layton (1681-1719) took out letters of administration in 1706 and ‘possessed himself of his father’s personal estate, to the amount of £40,000 and upwards’. He married Elizabeth, the daughter of John Hungerford Esq. of Doctor’s Common, Devon, and died in 1719 after a long illness, during which a number of wills and codicils were written to ensure that, on his death, his wife Elizabeth would inherit all his property and family jewellery, leaving his father’s pledges that his brother Robert, and the Cumberland Fishers would be provided for, unfulfilled. In 1722, the wealthy widow Elizabeth (1685-1731) married Peregrine Bertie Esq. of Low Layton (1688-1743), a branch of the family of the Dukes of Anchester, taking all the property, including Scale Hill, with her.

Scale Hill Hotel and Grasmoor (Abrahams Series) - Picture Postcard

Ann Langton (the granddaughter of Mr Robert Fisher) then brought a case in law against Elizabeth and her new husband, Mr Peregine Bertie, which failed in 1727 and the Cumberland Fishers were unprovided for. Peregrine Bertie died in 1743, leaving his property to his son and heir by Elizabeth, a son he had also named Peregrine (1723-1786). He was the owner of the woods at Scale Hill, Mr Bertie’s Woods, now known as Lanthwaite Woods.

Peregrine Bertie (1723-1786) had 3 sons and 4 daughters, by his first wife Catherine (1734-1770) but only three daughters survived him. He died in 1786, leaving his daughers as co-heirs to the main Lincolnshire estate, providing that their husbands take the name Bertie and have issue.

After their fathers death, the two eldest daughters married two Hoar brothers – and in order to inherit the Bertie estate, they both took on the surname ‘Bertie’. Captain Thomas Hoar duly became Captain Thomas Bertie. He had an impressive wartime naval career, becoming Admiral Sir Thomas Bertie KSO. He served with his friend, Horatio Nelson and spent most of his youth serving in the West Indies and off the American coasts during the American War of Independence, seeing action in a number of battles with the French. Thomas Hoar married Catherine during the period of peace, taking the surname Bertie in accordance with his father-in-law's will, and also used his time ashore to carry out experiments that led to the introduction of lifebuoys to the British Navy.

The second daughter, Elizabeth Bertie married Ralph Hoar but also failed to have issue, so Scale Hill and the other Brackenthwaite properties did not go with the main Bertie estate, but instead were settled on the youngest of the three daughters, Mary Bertie.

In 1782, during her father’s lifetime, Mary Bertie married Samuel Lichigaray (1751-1812) a merchant in Low Layton, Essex, and they had five daughters, but no sons.

Samuel was the nephew of Matthew Lichigaray, a very wealthy naturalised merchant of Low Layton and of Tom’s Coffee House on Russell Street, Covent Garden, London.

In 1744 Samuel had received a third share of Matthew Lichigaray’s estate, after some £20,000 plus an annuity had been disbursed to friends and other relatives. Samuel inherited Phillybrook House at Low Layton as his residence and continued the business in Low Layton and London, going into partnership with his nephew John Dunsford, in the name of Lichigaray and Nephew.

On the death of Peregrine Bertie in 1786, Samuel Lichigaray, by virtue of his marriage to Mary Bertie, became the owner of Scale Hill, the Great Lanthwaite Wood, High Hollings, Lanthwaite Green/Peel Place, Lanthwaite Gate plus lands and cattlegates in Rannerdale, and he was the owner of Scale Hill in 1800.

You can read more about the Bertie Family, and the descendants of Peregrine Bertie in ‘A Memoir of Peregrine Bertie Eleventh Lord Willoughby de Eresby’.

In 1804, Samuel’s partnership of Lichigaray & Nephew runs into trouble. Their reputation is ruined by the Nephew, John Dunsford, who gives a false reference of a foreign trader. The case was well-reported in the newspapers of the day, and the judgement was for £710 at the time. Whether it was loss of reputation or the losses that they suffered through trading, their partnership was made bankrupt on 14th July 1804.

The assignees sold all of Lichigaray’s property on 29th August 1804 by auction at Garraway’s Coffee House in Cornhill. The Brackenthwaite Estates were sold, and Scale Hill was described as:

“That well-known INN and FARM, called SCALE- HILL, Justly admired and resorted to on account of its beautiful situation, --- WITH A CONVENIENT INN, Barns, Stabling, Cow- Houses, Outbuildings, Six Grasses, and NINETEEN ACRES.”

Scale Hill had previously been let to Henry Hewitson for £52 per annum, with five years to run; he was also renting the 35 acres of Great Langthwaite Wood (Lanthwaite Woods). The successful bidder at the sale, a Mr Thomas Gaitskell Esq., offered £7,124 for the Brackenthwaite Estates and became the next owner of Scale Hill, with Henry Hewitson continuing as the innkeeper throughout. However, Mr Thomas Gaitskell wasn’t to own Scale Hill for long.

In 1803, the late Volunteer Corps of Bermondsey, Loyal Bermondsey, Newington and Rotherhithe agreed to unite and form one Corps under the title of The First Regiment of Surrey Volunteers. The Regiment was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gaitskell with Major Thomas Burne as his Second-in-Command. The Regiment was intended to carry out duties which were later to become the responsibilities of professional police and fire brigades.

Uniform was not to be worn except when on duty or on “military occasions”. When so worn the full dress uniform was obviously a colourful affair consisting, with embellishments and trimmings, of a scarlet jacket, white breeches, white waistcoat, black silk stockings, helmet with bear skin and regulation feather, and lastly black cloth gaiters. Hair was to be “powdered and dressed close”. Undress uniform was a lower key affair consisting of a blue jacket, white pantaloons and full dress helmet. You can read more about the 1st Volunteer Battalion on the Queen’s Royal Surrey Regiment website. To the right is a Mezzotint of Mr Thomas Gaitskell Esq. which is held in the British Museum.

Scratched below the image with the title in open letters and 'Lieu,t Col,,l Com,,t 5th,, Reg,,t Surrey Loval Militia // Painted by T. Stewardson Esq.r Portrait Pianter to her R.H. the Princess of Wales. // Engraved by W. Ward A.R.A. Engraver to their R.H. the Prince Regent & Duke of York. // Pub. Aug.t 1. 1815, by the Engraver 24 Buckingham Place, Fitzroy Square.'

Made by: William Ward After: Thomas Stewardson Published by: William Ward

Advertisement for the sale of Loweswater manor and lands, 1807

On 1st October 1805 Joshua Lucock purchased the Brackenthwaite estate, including Scale Hill, from Thomas Gaitskell for £7200.

Joshua Lucock, grandson and heir of Joshua Lucock of Cockermouth, had acquired Lorton Hall from the Peile-Barnes family in 1800, and had set himself up as the flamboyant Squire of Lorton, but his means were not very extensive at that time. In 1805 his maternal uncle, Joseph Bragg of Moseley Vale, died naming Joshua Lucock his residuary legatee. The amount is unquantified, but it included the land on which Grassendale Park, of the Liverpool Park Estates, was later built, and which he sold on for £13,000 in 1808. However, Joshua Lucock had to decide between receiving the money and property from his uncle, or keeping his name.

In May 1805 he duly became Joshua Lucock Bragg, and then set about the accumulation of a considerable estate in Lorton, Loweswater and Brackenthwaite, creating the Lorton Hall Estate.

In 1807 he purchased the manor of Loweswater, Thackthwaite and Brackenthwaite together with Holme Wood, Loweswater Lake and Riggbank, from the Wilfrid Lawson’s estate for £10,500. Separately he purchased Potter Gill in Loweswater, other property in Brackenthwaite, and several farms in Lorton. You can see the advertisement for the sale of the land.

A pre-industrial English village such as Loweswater had three long-established systems of supervision and control, each with its own court and officers; the manorial system, the church and the state. The manorial system controlled property and land use. The manor of Loweswater was the property, granted by the crown, for the lord of the manor. The manor had a boundary and the customary tenants had rights to use their farmstead or tenements subject to the customs of the manor, plus rights on the commons. The relationships among tenants and between tenant and lord, who each had rights and responsibilities, were managed through the Loweswater manor court and its officials. The state gradually took over as the main line of control as the two other diminished in importance. The long transfer to the state of church authority and responsibility dates to the reformation, but in Loweswater the manorial system functioned well in to the twentieth century. John Marshall (more on him shortly) resisted enclosure and division of the commons for nearly forty years, and on eventual enclosure in the 1860s Marshall did not enfranchise the tenants, keeping the property customary.

In 1809 Joshua Lucock Bragg of Lorton Hall died, leaving his wife Rebecca (nee Luck Wilkinson) and six children, the four eldest of whom had learning difficulties or special needs, including the heir, Raisbeck (1795-1850).

The estate was left in the hands of three trustees, excluding wife Rebecca, whose job it was to use the Estates as a source of funds to meet the bequests in Joshua’s will, and to keep the family in Lorton Hall. Much of the estate was in Chancery, until the last two Braggs died at Lorton Hall in the care of attendants in 1875. You can read more about the Luck Bragg family, and their final resting place at Lorton Church written by the Derwent Fells History Society.

The Bragg trustees held Scale Hill and the surrounding Estates until 1824, when John Marshall purchased the property.

Scale Hill Hotel, c.1800s

John Marshall had already been to Scale Hill, as a guest, in 1800. He had been on a trip with William Wordsworth and admired the building during his visit of the Lakes.

During the French wars, Marshall had become very wealthy through flax spinning in Leeds. When the French war re-started in 1803, Marshall benefited during it beyond his wildest dreams, seemingly through a practical and astute understanding of the principles of supply and demand where most other producers were the losers. His business had started well and at the beginning of the war he was worth around £40,000.

In 1810, John Marshall leased the mansion at Watermillock and then built Hallsteads on Ullswater as his country home, which was completed in 1815. He began to establish the Marshall estates and dynasty in the Lakes, choosing Buttermere, Crummock and Loweswater for himself, and seats at other lakes in turn for his sons. In 1814 he purchased from the Bragg trustees the Lordship of Loweswater and Thackthwaite, with the lake, Holme Wood and Riggbank. In 1815 he purchased the freehold estate of Gatesgarth and Birkness, attempting to own and control as much of the three lakes, their fishing and shores as possible.

By 1813, Marshall had accrued £400,000 into his flax spinning business employing over 1,000 people and, exploiting high prices to create high margins, Marshall was able to apply skilled management and foresight in raw material supply and productivity techniques to master the turbulent conditions and reap the rewards. By the end of the period, and through his own enterprise, Marshall almost held a monopoly on the linen trade in the UK.

By 1820 Marshall had made inroads in to London society and was investing strategically in the stock market. He founded a Lancasterian School, a Mechanics’ Institute and a Literary and Philosophical Society in Leeds, and made the first proposal for what would later become Leeds University.

At this time, Marshall also spoke with other local mill owners in a bid to set up schools in the Holbeck area for the children of the mill workers, or in many cases, the children who were also mill workers. Marshall developed a system whereby children would work at his mills and then be sent to the school, which was built in 1822 on the site of what would become Temple Mill, and was later incorporated into the design of the landmark building. Within ten years, when a second infants school was built, more than 2,000 children had passed through the school. Until the introduction of compulsory education in 1880, mill schools made a critical contribution to the literacy of the urban masses, and in Marshall’s case, his work was a sincere attempt to make life in a rapidly developing town like Leeds more viable for the labouring classes; offering them some independence, some ownership over their own destiny and some opportunity, beyond simply employing them.

A Coach & Horses brings Guests to Scale Hill, c.1800s

Loweswater School, now known as Loweswater Village Hall built by John Marshall MP, 1839

In 1824 Marshall purchased the Brackenthwaite estate from the Bragg Trustees, separating the enlarged Lanthwaite Wood from Scale Hill and keeping his woodland in hand, as elsewhere. In 1823 he had purchased Nether Close, just across the Cocker, also the site of the lead mines, to which he held the rights as lord of the manor. He combined the farming of this land with the tenancy of Scale Hill, allowing the buildings at Nether Close to become used for the management of fishing, forestry and game. By 1825 he had spent at least £34,000 on property in the local area.

In his latter days, the industrialist swapped mills for the House of Commons. He was voted into office representing Yorkshire in June 1826 and received the honour of being the first mill-owner to represent the interests of West Riding. He represented Yorkshire from 1826-1830. However Marshall’s life as an MP was short-lived; having fallen seriously ill, he retired from politics a year later and gave up his seat in 1830 when parliament was dissolved.

In 1839, under the title of Lord of the Manor, he had built Loweswater School which is now known as Loweswater Village Hall.

By the end of the French war, and at the age of 50, Marshall had realised many of his ambitions and had become a pillar of society; feared and respected, and seen as an example to follow. His life changed accordingly and he aspired to a social standing above that of simply a successful mill-owner. He accumulated country estates and town houses while keeping the business ticking over for his children. But he also thought hard about problems in society and sought to change them, becoming an educational pioneer and a Member of Parliament, activities that brought him both influence and social recognition.

Marshall had always been something of an intellectual, studying science in his own time as a youngster, which helped him with the development of bleaching techniques for linen and in the use of building materials for construction of his mills. He later developed an interest in geology and farming techniques, always appreciating that there was a rush of ‘modern’ knowledge he had to keep abreast of.

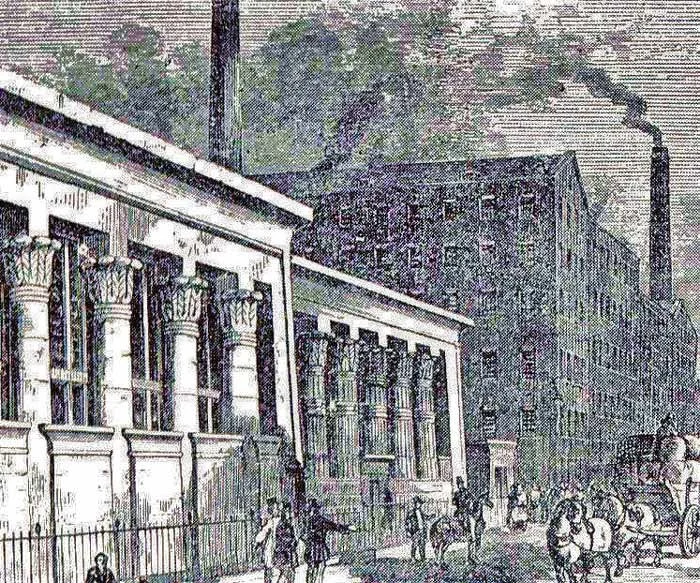

Marshall’s Temple Mill in Holbeck. The Grade I listed building was based on the Ancient Egyptian temples of Hathor at Dendera and Horus at Edfu and was opened 1843. Disraeli makes mention of it in his novel ‘Sybil.’

John Marshall’s purpose in acquiring the Brackenthwaite estates would have been different from the previous owners. His business in Leeds at that time generated a very large income, and his purchases in the English Lakes were for recreation and to establish a distinctive social position.

His interest was in natural scenery, and particularly in the creation and management of plantations in lake scenery. He shared this interest with Wordsworth and in 1807, when Wordsworth’s Guide Through The District Of The Lakes was in genesis, Marshall had toured North Britain and advised Wordsworth on the appropriate situation for the larch, to optimise the balance between value and aesthetics in Lakeland plantations.

In 1816, after purchasing Loweswater and Gatesgarth, but before owning Scale Hill, Marshall brought some friends there, as Sarah Hutchinson noted:-

William [Wordsworth] and I spent three days, the week before last, with Mr Marshall at Scale Hill, Lowess Water, Buttermere, & Crumock, viewing his estates and manor there, and planning his proposed plantations and Improvements. He is going to plant very largely by the side of the two last lakes – and, as he will only plant native wood, and in no wise sacrifice beauty to convenience, we expect that his labours will not only be profitable but ornamental.

Marshall’s plans were partly thwarted by the statesmen of Loweswater, or more precisely the owners of stints of Buttermere Scale, whose representatives Marshall met at newly-purchased Scale Hill on 17th August 1824.

Marshall proposed to enfranchise the tenants and reduce the commons to a stinted pasture, in return for Buttermere Scale and contiguous land along Crummock lakeshore. This unusual proposal would have left Marshall with much of the west bank of Crummock enclosed, to be planted with the intended trees, in exchange for freeholds, while the rest of the common would have remained undivided by fences.

It must have been unattractive to the Loweswater tenantry, and the other Buttermere Scale stint owners, because no enfranchisement or enclosure was agreed in his lifetime and the west bank of Crummock remained bare as a direct result.

At the beginning of the 19th Century, poachers were causing problems for the Lord of the Manor, John Marshall. In October 1838, he wrote to his agent, Richard Atkinson, to say that something had to be done and suggested that hand bills be spread around the village; he complained that the punishment for poaching was too small. A week later he was changing his mind. ‘If you have not got any hand bills printed, it may be sufficient to put up a written notice, in the Blacksmiths’s shop and church and School, that offenders will certainly be prosecuted.’ A committee against poaching had been formed at Cockermouth, and Marshall said firmly ‘I’ll spare no expense to stop it’. In the end he was called upon to pay out ten shillings each now and again to John and Richard Clerk for ‘watching fish in the night’ with no indication of any great success.

A Warning To Poachers, from The Marshall Estate, Scale Hill, 1839

Mrs John Marshall, MP

To be the tenant of Scale Hill with John Marshall as landowner must have been a mixed blessing. Marshall used the Inn frequently as his base in the Western Lakes when visiting his estates, alone or with guests, and so money would have been available to develop and refurbish the property to the high standards he would expect. But at the same time he was a keen supervisor of detail, who would expect high standards of service from his tenant at Scale Hill. The result, however, was of benefit to the travelling public and for the reputation of the Inn for high standards. There is a great deal of recorded evidence of that reputation:

CRUMMOCK-WATER

Is about one mile from Buttermere; it is three miles long, and, on the average, half a mile broad. It is bounded on all sides, save the north, by lofty mountains; and about a mile beyond the foot of the lake, at Scale Hill, is a most excellent Inn, where the traveller of any grade will find good living, cleanliness, and civility, with the most reasonable charges. The angler or artist will find this house delightful head-quarters, from whence he may visit the neighbouring lakes of Buttermere, Crummock-water, and Lowes-water : the fishing in all these lakes is capital, more especially for pike.

Notwithstanding the tyrant pike are so abundant, these waters are well supplied with trout from their numerous small tributary streams. The views from a lofty wooded hill close to the Inn are of the most sublime description; and that in particular from a seat called after John Marshall, Esq. (the proprietor of this fine estate), is one of the most magnificently beautiful in this romantic region. Scale-force is a fine waterfall, about a mile from Crummock-water, and is well worth visiting. …

Ennerdale-water, Wast-water, Elter-water, and Devock, may be visited en route from Scale Hill; and of these lakes, all containing trout, the last-mentioned will be found to produce the largest, the reddest, and best-flavoured trout in Cumberland.

(Hofland, TC The British angler’s manual: or the art of angling in England, Scotland, Wales & Ireland. London Bohn, 1848 pp.306-7 )

You can still visit the site of Marshall’s Mill today in Holbeck, Leeds, which is now a Grade II* Listed Building.

It was originally a four-storey mill, drawing water from the nearby Hol Beck. A Boulton & Watt steam engine was installed to assist water power. It was to eventually supplant Yorkshire’s previous cottage industry of hand driven spindles.

Temple Mill, constructed in the form of an Egyptian Temple, was built between 1838 and 1841. Later, the complex employed over 2,000 factory workers and was considered to be one of the largest factories in the world, with 7,000 steam-powered spindles.

Many reports claim that Marshall treated his workers better than most factory owners: overseers were forbidden to use corporal punishment to control the workers, and Marshall installed fans and attempted to regulate the temperature of the mill. In 1844, Marshall and a neighbouring engineering firm, Taylor, Wordsworth and Co broke new ground by organising an away weekend in Liverpool for their workers, a novelty which caused even the editor of the normally liberal Leeds Mercury some concern:

'Entirely approving of excursions for the working class, and with the kindest feelings towards the workmen of Messrs Marshall and Messrs Taylor and Wordsworth, we would express our earnest hope that the Sunday spent in Liverpool may not in any respect be spent in a manner unbecoming the day ... There are many excellent men among the above bodies of workmen, and great responsibility will rest upon them for the issue of this new and somewhat doubtful experiment, of a large body of people being away from home on the Sabbath, and on two whole nights.

Marshall & Sons ceased production in 1886 and the site was taken over by other textile producers. You can read more about the story of the Marshall empire here.

Notable Visitors At Scale Hill During The Marshall Years

Harriet Martineau (1802-1876), visits Scale Hill July 1845.

Dorothy Wordsworth (1771 – 1855) visits Scale Hill in 1816.

William Wordsworth (1770-1850) visits Scale Hill in 1800 with John Marshall and many more times in the 19th Century. He describes it as a ‘roomy Inn with very good accommodation’ in his Guide To The Lakes, first published 1810.

There were many notable visitors to Scale Hill during the Marshall Years. John Marshall’s social standing, as well as the tourism boom led by the likes of The Romantics, such as Wordsworth and Coleridge had created a huge amount of interest in the Grand Tour of the Lake District. When the Lakes were ‘discovered’ in around 1750, as an English version of the Arcadian Grand-Tour, it was the scenery around Derwentwater which provided the main focus. By 1770, Buttermere, Crummock, Loweswater and the Vale of Lorton has been included, and Scale Hill developed as the recommended stop for the gentry tourists travelling from Derwentwater and Keswick.

Harriet Martineau, William Wilberforce, and William and Dorothy Wordsworth who were both friends of The Marshall Family visited, as well as likely visits by artists such as JMW Turner and Edward Lear who were visiting the area to paint the dramatic landscapes and views which are still so widely admired today.

Early Guide Books

The success of Scale Hill was assured by Thomas West, who wrote the definitive guide to the Lakes, first published in 1778, which became the standard compendious work for the next fifty years. West advised:-

From the Bridge at the foot of the lake [Crummock], ascend the road to BRACKENTHWAITE. At the hedge ale-house, SCALE-HILL, take a guide to the top of the rock, above Mr BERTIE’S woods, and have a view of CRUMMOCK WATER entirely new. The river COCKER is seen winding through a beautiful, and rich cultivated vale, spreading far to the north, variegated with woods, groves, and hanging grounds, in every pleasing variety.

Thomas West (1720 – 10 July 1779) was a Jesuit priest, antiquary and author, significant in being one of the first to write about the attractions of the Lake District. Partly through his book, A Guide to the Lakes, the Romantic vision of the scenery and wilderness of the north of England took hold, ushering in a period of continued tourism in the Lakes.West had travelled widely throughout continental Europe, and after accompanying various parties visiting the lakes, decided to write a detailed account of the scenery and landscape.West set out to create a guide that would be of particular use to artists, writing in his introduction that he aimed

'To encourage the taste of visiting the lakes by furnishing the traveller with a Guide; and for that purpose, the writer has here collected and laid before him, all the select stations and points of view, noticed by those authors who have last made the tour of the lakes, verified by his own repeated observations. '

To this end he included various 'stations' or viewpoints around the lakes, from which tourists would be encouraged to appreciate the views in terms of their aesthetic qualities. Published in 1778 the book was a major success. As well as being the first guidebook to the lakes, West was amongst the first writers to challenge the view of the wild and savage north, and his book was one of the first to stress the notion of the picturesque environment. It was particularly influential at a time when Grand Tours were popular, as West claimed the Lakes contained much of the scenery that could be enjoyed on the continent, likening it to the Alps. His book was followed by similar works by William Gilpin, Uvedale Price and William Wordsworth. West's book was the beginning of the era of 'true tourism' in the Lake District. It followed on from Dr John Brown's assessment in 1753 that the 'perfection' of the area rested on 'Beauty, horror and immensity', and challenged Daniel Defoe's interpretation of it in 1698 as the 'wildest, the most barren and frightful' place he had ever seen. Despite criticism and satirical spoofs of both the prose of the guides and the attitudes of the tourists they attracted to the Lakes from the likes of Thomas Rowlandson and William Combe, the book ran to seven editions before the turn of the century.

It was to be West's last work. He collected material for the second edition, but died a year after the book was first published, on 10 July 1779 at Sizergh Castle, Westmorland. He is buried in the Strickland family chapel, at Kendal Parish Church.

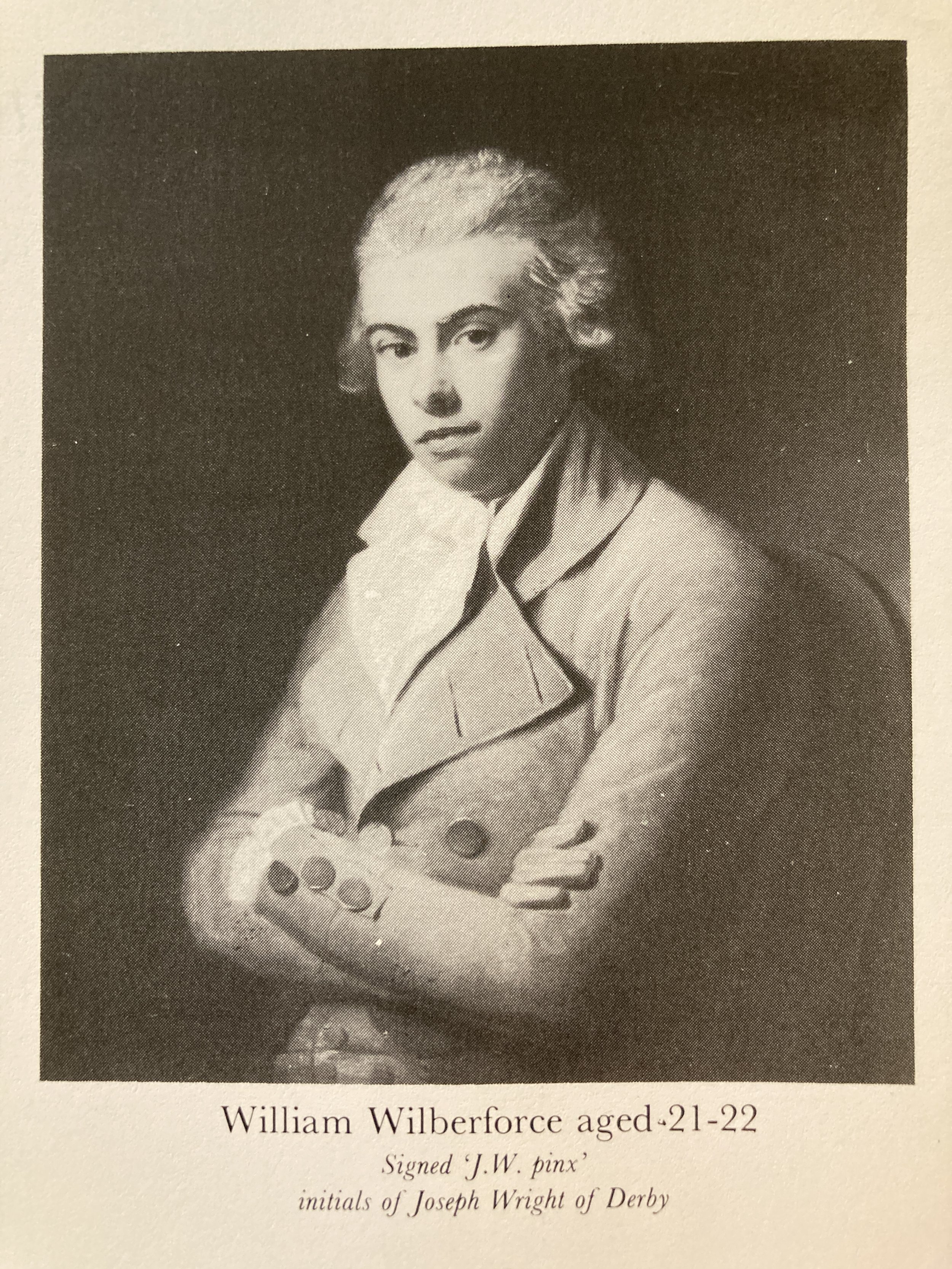

William Wilberforce

A memorial statue of William Wilberforce, Hull

It seems very likely that William Wilberforce had read Thomas West’s account and followed it when he visited the Lake District in 1779. Aged 20 years old and an undergraduate of St. John’s College, Cambridge, Wilberforce embarked upon a journey from Cambridge to the Lake District, chronicling his travels in a journal which provides the earliest and the fullest description of his many visits to the Lake District.

In ‘Journey To The Lake District From Cambridge - A Summer Diary, 1779’ Robin Birkenhead comments ‘It is also unusual in that on this occasion he had no preoccupations, no art of retainers and relations accompanying him, nor any plan except to immerse himself in the beauty of the scenery.’ He continues ‘Several of his days in the Lake District ended with him ‘wet to the skin’. He must also have been cold, famished and exhausted. In these conditions it is no easy matter to settle down under the miserable light of a candle and record the events of the day at some length. To make matters worse, even in 1779 his eyesight must have been poor'.

In spite of these handicaps his approach to the journal is meticulous. The reader is given detailed instructions as to his route and is even told where to stand for the best view. The dimensions of mountains and waterfalls are given or guessed at in the absence of reliable information; old country tales are retold. It reads as if he was preparing a guide book to the Lakes.’

Wilberforce leaves Cambridge on July 10th 1779, travelling up to Hull, across to York, through Harrogate, Ripon, Aysgarth, Hawes, Ingleton, Lancaster, Ulverston, and Ambleside, arriving at Keswick on September 3rd 1779. He plans to meet his friends in Keswick, and at by this point has already travelled 410 miles - 75 by water, 110 by chaise and 225 on horseback. Some two-thirds of the time he had spent making visits en-route, and his actual travelling averaged about 26 miles a day. Of those he met in Keswick only two are certainly known, the first, a Mr Thomas Gisborne, a college friend, who became a warm and sympathetic fellow-campaigner for Wilberforce. The second, a Mr William Cookson, also a fellow undergraduate at Cambridge who was engaged in a mercer’s business in Penrith. His sister had married John Wordsworth and given birth to the poet at Cockermouth nine years earlier.

~

Wilberforce visits Scale Hill twice during his trip in 1779, enjoying Bacon & Eggs and taking shelter during a rain storm. His entries below, read:

Thursday September 9th 1779

Set out between 7 & 8 with Gisborne & Tom Hutton, to Buttermere. Passed thro’ Portingscale & through the delightful Vale of Newlands. The Vale becomes less smiling as you proceed, till you come to where it appears to close up, the Hills on each Side & those in front very high. In your way to this place you have a very fine View of Catbells, Lady’s Bower etc., viewing them on the Side contrary to that which you see from the Lake. The Passage through the Mountains where it appears to be clos’d up is called Newlands Hawse. On the Left is a Waterfall & a little Bason in the Rock from whence it is fed. In front a very great Waterfall. Go through the Hawse & you have a most striking Scene of Wildness & Desolation. A new collections of Mountains surrounds you. This road has been improv’d since West’s Account. Before you reach Buttemere you see a very great Waterfall pouring down from one of the Hills which is near the Lake. When we got to the Ale House we went to the left by the Side of Buttermere, dismounted & walk’d close to the Water. The Lake is a small one & the Mountains rise directly from the Lake as Perpendicular as a Wall, & of an immense height opposite to them are very high Rocks not close to the Water. The Road to the left proceeds into Borrodale by Honistar Crag and the Wadd mine.

Return’d & went through the village of Buttermere.

(Goose Gate is a Right of putting & fatting two geese on the common, Whittle Gate is a right of dining with his parishoners by turns every Sunday, Harden Sark such as the Carters use & clog & two strong Shoes annually.)*

The lake of Buttermere one of the most savage ones I saw. It has Char in it & fine Trout. To Crummock water, took a Boat across the Head of the Lake & proceeded on foot by the side of it a little way; went about ½ mile up on the Left just before we came to Mellbreack to see a Waterfall. There is a Stone Wall which will carry a stranger to it. It is in a Cleft of the Rock about 2 or 3 or 4 yds. Over, & it falls perpendicular about 30 yards as I imagine, the Country People say much more. After it has fallen it proceeds in the Cleft about 20 or 30 yds. Where it falls for 10 or 12 feet into the open Valley. To see it properly climb up beyond the first fal. Whilst we were there it grew so thick that we could scarce see across the Lake & a drizzly rain fell so that we could just discern Grassmire a vast red Hill standing opposite Mellbreak. They look like guards on each side of the Lake. Went to Scale Hill, got some Eggs & Bacon & rode home. The Vales of Lorton and Brackenthwaite were seen to a sad disadvantage. Came into the Whinlatter Road at the 6th Mile Stone. Saw Bassenthwaite below us on the left.

*Goose Gate, Whittle Gate etc. - West mentions ‘clog-shoes, harden-sark, whittle-gate and goose-gate’, sceptically, as perquisites of the incumbent of the parish.

Saturday September 18th 1779

Thought of setting out in the Morning, when there came on a most violent storm of Wind & Rain with thunder & lightning. (A man was once shot dead from the Castle at a place which must be near ¾ of a mile off.) Cookson & I in the afternoon took a Ride as far as the end of Crummock Water & walk’d up (according to West’s direction) above Mr. Bertie’s Woods. The View is of a very fine valley water’d by the Cocker which appear’d to great advantage from having overflow’d its Banks & made new swells & bends. West’s description of the View is very exact & good. Grasmire frowns awfully behind on the Left & Mellbreak on the Right. A pretty View of that side of Crummock & the valley between it & Loweswater, part of which is visible. While we were out were 2 Violent Storms of Rain & Hail but we luckily took Shelter in Scale Inn. We had not time to go to the House West speaks of by the Gate leading to Ennerdale. It was dark before we reached Cockermouth & the wind cold and uncomfortable. The Ride about 15 miles.

~

William Wilberforce's greatest political achievement was his long fight to end Britain's involvement in the Transatlantic slave trade. Wilberforce achieved the suppression of the slave trade, with the passing of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Bill, in 1807. He remained concerned about the many people still held in slavery and carried on his campaign until the bill outlawing slavery in Britain and all its colonies was passed in 1833 - just days before he died.

Wilberforce also devoted himself to other causes and campaigns such as the limiting of the hours children should work. Like his contemporary, Quaker campaigner Elizabeth Fry, he fought for prison reforms, and he was also passionate about policing, education, healthcare and issues caused by gambling. He appealed for amendments to the Poor Law (to improve the conditions for the poor) and in 1796 became a founding member of the ‘Society for the Bettering Condition and Increasing Comforts of the Poor’. This organisation worked to reform Parish Relief and Workhouses for the poor and improve their general living conditions.

Wilberforce was one of the founding members of the RSPCA (the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). He was also instrumental in forming the Proclamation Society which was dedicated to promoting virtue in public life. Their aim was to make the idea of humanitarianism popular.

It is estimated that almost 70 separate causes were significantly advanced by Wilberforce's involvement. Although he enjoyed a successful political career, Wilberforce, a deeply religious man throughout his life, put his many achievements down to ‘God’s will’ rather than his own merits. You can read more about his life and achievements here.

JMW Turner

This view that Thomas West describes, is the familiar one at the top of what we now call Brackenthwaite Hows. It seems very likely that Turner would have visited Scale Hill, since he went up to the ‘Viewing Station’ at the top of Brackenthwaite Hows which was, at the time, part of the Marshall Estate. In order to access this view point, one of the guides, employed by Scale Hill would have accompanied the tour party through Lanthwaite Woods (Mr Bertie’s Woods - named after Peregrine Bertie) and up to the summit of the Hows in order for Turner to capture this view.

From this view, Turner took notes and sketched out the scene, naming it Crummock Water, Looking towards Buttermere, in 1797. This work (left) is held by the Tate Collection and the sketch formed a basis for the work (above) Buttermere Lake, with Part of Cromackwater, Cumberland, a Shower which was exhibited a year later, at the Royal Academy in 1798 to much critical acclaim.

Lucy’s Diary

Lucy in 1834, aged 31

Lucy Copland was born on 16th March 1803, the fourth child and only daughter of Alexander and Lucy Copland . In 1801 her father purchased land that had formed the major part of Princess Amelia’s Gunnersbury estate in Ealing for £10,000. He immediately set about erecting the house in which Lucy was born, Gunnersbury Park.

As members of Ealing’s most affluent society, the family entertained extensively and Lucy grew up in an environment that hosted grand garden parties, festivities and activities such as cricket and archery.

John Quincy Adams, later to be America’s 6th President, records in his diary of 21 September 1816 how he “walked to Mr Copland’s at Gunnersbury. There was a cricket match of about twenty young men upon his grounds”. He describes partaking of a lavish cold lunch, returning to watch the cricket till dusk and then repairing “to the portico, a detached building near the house where they have a billiard room” where “an elegant dessert was there set out, and the ladies, wives and daughters … and some others joined the party.” He continues with a walk around the grounds, set “in the most beautiful style of English ornamental gardening”, and returns to watch the fireworks over the lake. Whilst he played whist with friends, the “young people danced country dances until midnight”. Lucy would have been 13 at the time of Adams’s visit and by 1819 may have had the opportunity to enjoy the dances for herself.

Although there were several women diarists in the Regency period, it is believed that Lucy is the youngest. Aged 16, she records her daily impressions and experiences as she, her parents and her brothers, set out from London in their family coach on a mammoth tour of Wales, Scotland and the Lake District.

On Saturday 7th August 1819, Lucy Copland, aged 16, visited Scale Hill with her family. Her diary entry reads:

Saturday August 7th

We started at 11 o’clock for Scale Hill stupendous barren mountains in both sides are the only objects on the road 12 miles till within one mile of Scale Hill we caught a fine view of the ?***? & the Cheviot Hills when we arrived the gentlemen

met us & after some refreshment proceeded to Crommick Water three miles in extent encompassed by rugged pyramidal craggy mountains all defined by different names which our intelligent guide did not fail of telling us & we landed across the lake and surveyed the waterfall of Scale Force situated in a narrow chasm of rocks it falls 180 feet perpendicular with trees interspersed & is very fine; we then walked across some fields to the house where the celebrated Mary of Buttermere formerly lived we then mounted a hill to obtain a fine view of Buttermere a small lake

encompassed with mountains we then took to our horses & proceeded on a very bad road to the vale of Newlands the entrance is excessively fine we were surrounded by immense mountains & larger cliffs till by a turn of the road we had a fine view of the vale nine miles passed most delightfully in surveying this fine scenery when we arrived at Keswick to a late dinner.

Gunnersbury Park was purchased by Nathan Mayer Rothschild in 1835. Follow the link to learn more about Lucy’s fascinating life and the wonderful research of Lucy’s Diary.

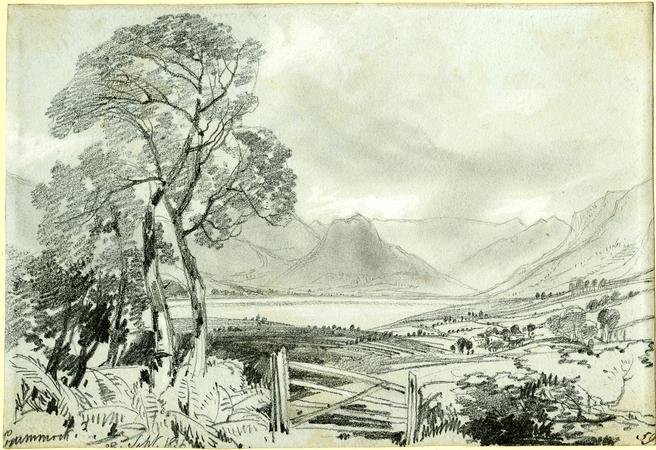

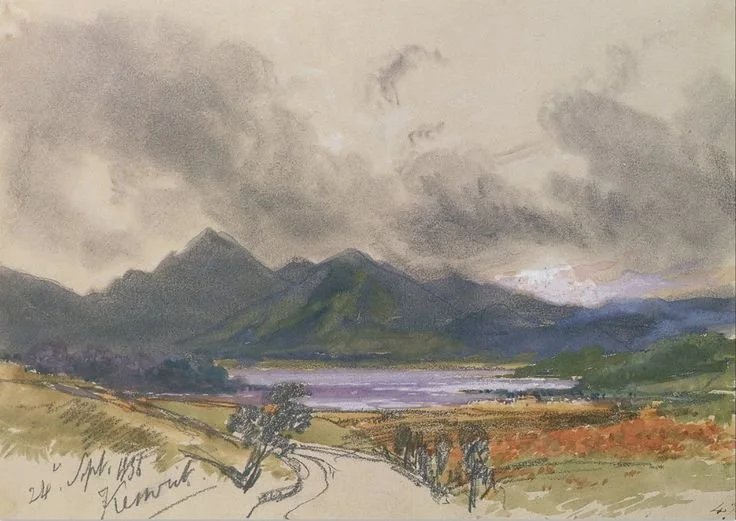

Crummock Water, Cumberland by Edward Lear, 1836.

Honister from near Buttermere. 27th September, 1836, by Edward Lear

Derwentwater, looking into the Jaws of Buttermere, by Edward Lear, 1836

A Waterfall in the Lake District by Edward Lear, 1836

24th September, 1836, Keswick, by Edward Lear

With thanks to the Derwent Fells Local History Society and the below sources without which this account would not have been written:

Vivien Noakes, Edward Lear – The Life Of A Wanderer – London 2006

Excursions to Loweswater (1865) – London 1987

Victoria and Albert Musem – The Discovery of The Lake District – 1984

An unpublished paper by Mr Michael Broughton on Lear In The Lake District – 2006

William Wordsworth ‘Guide To The Lakes’ – 1835

Royal Academy – Edward Lear 1812-1888 – 1985

Parson and White – Directory of Cumberland and Westmorland – 1829

Edward Lear’s Crummock Water

It was in August-September 1836 Edward Lear visited the Lake District. Lear wanted recognition as a serious artist, but became famous eventually as one of the best loved nonsense poets in English, and his letters are full of jokes from his three months tramping about the region.

Lear left Knowsley Hall, the Lancashire home of the Earl of Derby, in the second week of August 1836. He was armed with letters of introduction and used them to visit a series of country houses in north Lancashire in the following four weeks. These comprised the Hornby family in Lancaster, the Howards at Levens Hall, the Websters at Eller How near Grange-over-Sands, the Braddylls at Conishead Priory near Ulverston, the Upton family at Ingmire Hall near Sedbergh, the Nowell family at Underley Hall near Kirkby Lonsdale, the Greenes at Whittington Hall, also near Kirkby Lonsdale, and the Bolton family at Storrs Hall on Windermere. Letters survive from Levens and Whittington which, together with surviving dated drawings, have enabled a partial reconstruction of the itinerary. Lear was at Storrs Hall from the 7th to the 9th of September, and from there commenced a tour of the Lake District.

While no journal exists for those 10 weeks, there is correspondence in a dedicated archive. One published letter, written after his return, is to his friend and publisher John Gould on the 31st October ‘…it is impossible to tell you how and how enourmously I have enjoyed the whole Autumn. The counties of Cumberland & Westmorland are superb indeed, & tho’ the weather has been miserable, yet I have contrived to walk pretty well over the whole ground, and to sketch a good deal beside…”

Lear travelled alone, but whose guide was in his hand? He must have read Wordsworth’s Guide in the last and fifth edition of 1835 and perhaps Leigh’s Guide to the Lakes and Mountains of 1832. Who suggested he should visit Loweswater, and suggested, as is the fact, its water and hills are best seen from Waterend? Where did Lear stay during those weeks and how did he travel, other than on foot? From the dated sketches we know he was on the Kendal-Bowness road at Windermere on 10th July, Loweswater on 28th September, Grasmere on 5th October and other places in between, returning to Knowsley the country seat of the Earl of Derby where he had spent five years on and off drawing. He was back in London at the end of the year with his older sister, Ann, in their Southampton Row set of rooms. With the known dates his itinerary could be reconstructed and guesses made of inns for the overnight stays. In 1836 Scale Hill, described by Wordsworth as a ‘roomy Inn, with very good accommodation’ was offering meals and beds and if he was following Wordworth’s guide, it seems more than likely that he would have stayed in this recommended Inn.

Unfortunately, Lear destroyed his diaries and journals of the early years in 1840. These would have covered the period between 1832 and 1837 during his travels to Cumberland and Westmoreland. One authority on Lear, Michael Broughton, summarises the drawings: ‘an unique record of the Lake District is achieved by the use of pencil, chalk, stump and with some heightening in Chinese White on grey blue paper’. The most recent, and best biographer Vivien Noakes, comments, “many of the Lakeland drawings, done in bold, swirling graphite and soft chalk, demonstrate a new, powerful and exuberant artistic freedom” With those materials, with the sketch book in his knapsack, Lear on 28th September 1836, draws Loweswater.

There are two drawings, the first, dated, is a fine study of the lake, Melbreak, distant fells, foliage, trees, fields on either side, water and atmospheric cloud. The road runs close to the shore, and is hardly visible thereafter. There are many more trees today but it is visibly Loweswater. The second drawing is very different. With the top-hatted man and the bonneted child in the foreground, this seems to be mid morning, the sun casting defined shadows of the two boulders, large and small on the roadside, the figures and the trees. Lear’s output was so prolific that it would be nothing strange for the bespectacled 24 year old man to reach Loweswater near to Waterend by, say, 9am and in the morning make two sketches from different ‘stations’, and walk on in the afternoon to Ennerdle, taking the route over Fangs Brow, Lamplugh and Kirkland as the Wordsworth’s Duddon Valley excursion in late September 1804. And so to sit on the lake shore and do a preliminary draft of the long view down to Pillar. The Ennerdale drawing is dated 29th September and on the 30th he is in Buttermere for a panorama. Four days later he is on the way to Grasmere, and depicts Thirlmere. Grasmere from Red Bank gets the Lear treatment 5th October and Rydal Water on October 7th.

These dates – from the drawings of the ten-week tour tell of the seated hours of young Lear who loved walking, mountains and Romantic scenery. And tese hold for us his experience of quiet contentment. “It is safe to assume the numbered sequences is well in excess of 107 drawings” comments Michael Broughton. That is equal to one and a half drawings a day. The likely routes, to achieve this number of drawings, over road and track suggest for late September a number of inns where board and bed were available. If it was an inn convenient for Buttermere, Crummock and Loweswater, why not Scale Hill Hotel? This seems the most likely choice as one guide book that Lear was following, recommended it. The ease of access provided by the guides who were employed by Scale Hill Hotel to row tourists to Scale Force in the boats, is also a factor. At the time, it was only Scale Hill boats that would row tourists from Crummock Water up across to Hawse Point, and over to Scale Force. The boathouse still stands today at the foot of Crummock Water.

Wastwater, 1836, by Edward Lear

Harriet Martineau Visits Scale Hill, July 1845

Harriet Martineau was a remarkable Victorian. Feminist, political economist, writer and social reformer, she arrived to live in The Lake District at the age of 43, and knew that she had found her eden. ‘A Year At Ambleside’, first published by an American magazine in 1850 celebrates the beauty of her surroundings and provides a unique picture of a rural Victorian Lake District world. Martineau lived at ‘The Knoll’, the house she built in 1845 and where she remained until her death in 1876 kept many first hand accounts - letters and diary entries of the people who visited her including Charlotte Bronte, Wordsworth and Emerson.

‘Harriet Martineau at Ambleside’ by Barbara Todd fleshes out other details of the life of this courageous and energetic woman who, in the words of Florence Nightingale, ‘was born to be a destroyer of slavery, in whatever form, in whatever place, all over the world, wherever she saw or thought she saw it’.

In Martineau’s ‘Complete Guide To The English Lakes’ published in 1855, she retells the epic journey across Blake Fell. This adventure ends, as any good one does, taking Afternoon Tea at Scale Hill: “As we sat at our tea, in curious masquerade fashion, at the hospitable Scale Hill Inn, dressed in such odds and ends of clothes as the people could spare us while our own were drying, (our very knapsacks being wet through), we thought over our last two days of travel, and felt as if the calm sunset at Calder Abbey were enhanced in its charm, when we looked back upon through the storm on Blake Fell.” You can read the whole exciting adventure here, as written by Martineau.

Scale Hill Hotel, Brackenthwaite, 1900.

In 1879, Adam & Charles Black publish ‘Black’s Picturesque Guide to the English Lakes’, noting ‘Extending the excursion to Scale Hill, four miles and a half from Buttermere, the road traverses the north-eastern shore of Crummock Water, passing under the hills Whiteless, Lad-house, Grasmoor and Whiteside. Melbreak is a fine object on the other shore. From the foot of this mountain a narrow promontory juts into the lake, the extremity of which, when the waters are swollen, becomes insulated. A short distance before Scale Hill is reached, there is a fine view into the sylvan valley of Lorton. At Scale Hill there is a large and comfortable inn, which for a few days might advantageously be made the tourist’s residence. * There are walks cut through Lanthwaite Wood, commencing at the inn door, and running some distance by the side of the lake. One of the outline views is taken from this wood, the whole of which, as well as Loweswater Water, and one-half of Crummock Lake, belong to Mr Marshall. There is a lead mine in the neighbourhood of Scale Hill. Boats may be had upon Crummock Lake, from which the inn is about a mile distant, and Scale Force may be visited, if not seen previously. One boating excursion at least ought to be taken, for the purpose of viewing the fine panorama of mountains which enclose the lake, and which can nowhere be seen to such advantage as from the bosom of the water. from the Lower extremity, Rannerdale Knot and the Melbreak promontory seem to divide the lake into two reaches. Whiteside and Grasmoor are majestic to the highest degree.

*There are also two or three houses fitted up for the accommodation of visitors.

Buttermere Coach on its way up Buttermere Hause from Keswick

A typical Victorian coaching party from Buttermere to Keswick over the passes

A coaching party descending Buttermere Hause

“Solitude” - Crummock Water, Abraham, 1935

In 1888, Henry Irwin Jenkinson, F.R.G.S writes the ‘Tourist’s Guide To The English Lake District’ and recommends that:

‘On arriving at Buttermere, take a boat for Scale Force, and arrange for the carriage to meet the boat at the Hause Point, which is on the East side of Crummock Lake, 1m from Buttermere. Those who desire to sail the entire length of the lake, can send the carriage to Scale Hill Hotel, which is from the North end of the lake. It is a good hotel, and if luncheon has not been taken at Buttemere, it ought to be taken here…Those who visit the hotel, and have half an hour to spare, should walk to the “Station,” a height situated in the Lanthwaite Wood, commanding a magnificent view. It is situated 300 yards from the inn. After entering the plantation at a gate near the south end of the house, and walking a few yards, a foot-path on the left will be seen, which winds to the top of the hill. Below is spread almost the whole of Crummock Lake, with Mellbreak, Red Pike, High Stile, and Rannerdale Knott rising from its shores.”

The Folder Sisters

Hannah Folder and her sisters, Mary and Martha on the Terrace at Scale Hill, c.1910

Scale Hill Hotel, late 1800’s

At the end of the 1800s-early 1900’s, Scale Hill was run by Hannah Folder and her sisters, Mary and Martha. Here you can see them pictured at Scale Hill, outside on the Terrace. These French doors and the steps down to the terrace still exist!

Hannah and her sisters ran a very successful establishment throughout the Victorian era. It was still owned at this point by the Marshall Estate, but the Folder sisters had a returning set of visitors who would often visit, year in, year out. One of these groups were known as ‘The Easter Gentlemen’. You can see them on the terrace with Hannah and her sisters, below.

Guests enjoying the views from the Terrace at Scale Hill

Staff outside Scale Hill, late 1800s

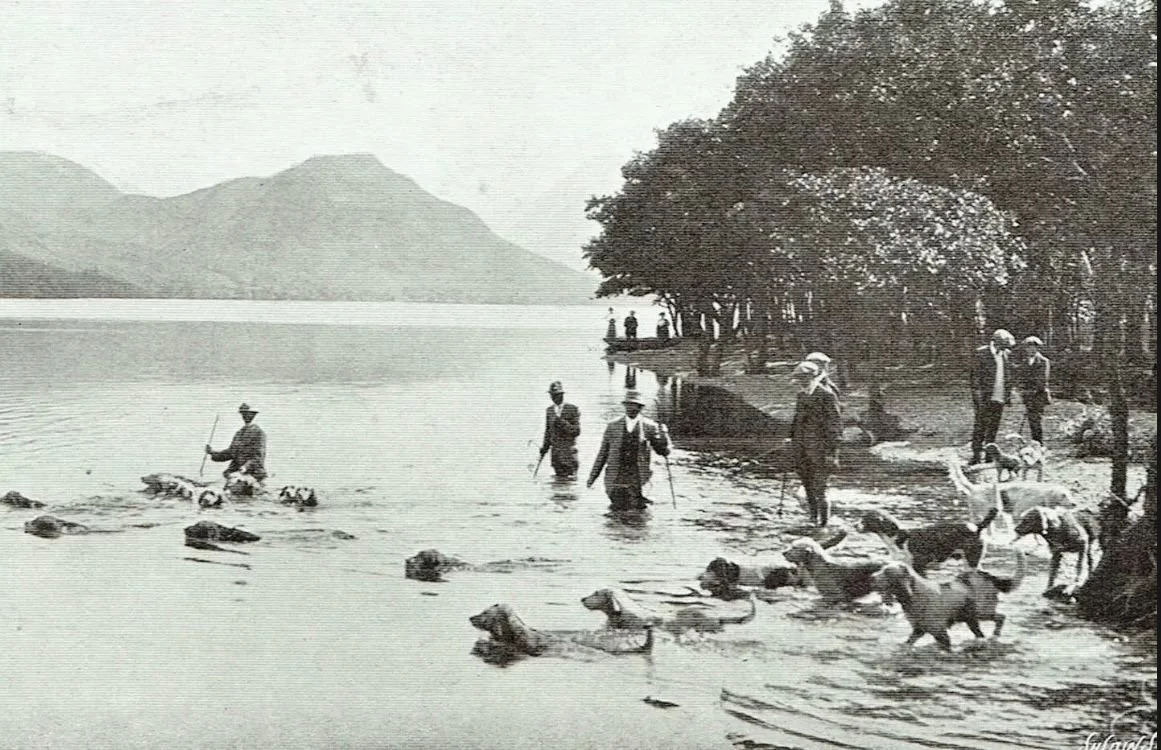

The West Cumberland Otterhounds, 1911

By the turn of the 20th Century, Scale Hill had become renowned with the carriage trade and those who were seeking adventure. For those guests who would visit, a light lunch or a hearty supper awaited them at the end of their days exploring the local area as well as Wines, Spirits and other Soft Drinks.

The Folder Sisters were dedicated to Scale Hill, and having all being raised in Loweswater knew the locals and the area very well. They were the perfect Landlady for the Marshall Estate, who were not as closely linked to the vicinity as they once had been at the beginning, under John Marshall’s steady watch.

Guides were still employed by the Marshall Estate at this point, and Scale Hill owned the Rowing Boats which were kept at the Boat House on Crummock. These boats would row the visitors over Crummock Water, stopping at Hawse Point and at Scale Force.

As well as attracting visitors to the area, Scale Hill also welcomed the locals and the Inn was an important part of the local community. You can see below the West Cumberland Otterhounds Hunt meet at Scale Hill, with Mr Armstrong and Herbert Stokes on the Terrace at Scale Hill. Such local hunts would attract followers from other parts of the country and Scale Hill would host the guests as they followed the Hunt.

Mr Armstrong, Joint Master of the West Cumberland Hunt and the huntsman, Herbert Stokes on the Terrace at Scale Hill, 1911

The West Cumberland Otterhounds cool off in Crummock Water, 1911

The Howett Worster Era 1931-1932

Scale Hill remained in the Marshall Estate until 1931 when it was purchased by Alexander Howett Worster. He owned the Hotel from 1931 - 1932. He was a stage actor and had just recently finished playing in the Original London West End production of Show Boat at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.

During this time, a number of famous stars of Broadway and the West End Stage visited the Hotel. Show Boat was a huge commercial success, with Edith Day having come over to the London production from Broadway. It also launched the career of Paul Robeson, who was an American bass baritone concert artist, stage and film actor, athlete, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for his political stances.

Listen to Howett Worster singing a duet with Edith Day - Why Do I Love You and Make Believe from Show Boat.

Howett Worster on the Terrace at Scale Hill, June 1932

George Gerard Storey & Air Chief Marshall Sir Augustus Walker

Howett Worster and Gerard Storey, June 1932.

Air Chief Marshall Sir Augustus ‘Gus’ Walker and Mr Paul Warrington

Visitors arriving to Scale Hill in an Armstrong Siddely with an RAF Emblem

These pictures of Howett Worster, Paul Warrington, Gerard Storey, Wilfred Gibson and Gus Walker were taken during a trip to Scale Hill in June 1932.

Shortly after graduating from Cambridge University, this group of friends toured the UK, and during their trip fo the Lake District, stopped off at Scale Hill, staying at the Hotel for a few nights. Gus Walker was born in Leeds but educated at the nearby St Bees School, in Cumberland, so we think he would have had some local knowledge and was acting as the groups ‘tour guide’.

Here they are pictured as young men, but Gerard Storey and Gus Walker were to go on to be recognised as heroes of WWII.

On the night of 16th June 1943 George Storey was the pilot and squadron leader of the 49th Squadron as they flew a bombing raid to Cologne. He was 32 years old and this was only his second tour.

His squadron flew out of RAF Fiskerton in Lincolnshire. Upon their return journey, his Lancaster ED785 was shot down by Luftwaffer night fighter pilot Rudolf Frank over the Scheldt Estuary near Flushing, Holland.

His body was recovered from the sea near Westkapelle on 21st June 1943. He is buried along with five of his fellow crew members in Flushing Cemetery at Vlissingen, Holland.

You can learn more about Air Chief Marshall Sir Augustus Walker and we would welcome any further information about this group of visitors. With thanks to Paul Warrington for sharing these wonderful pictures of his father and family friends.

The Milburn Era 1932-1966

Alexander Howett Worster owned Scale Hill Hotel until it was put up for sale in 1932 and purchased by our Great-Uncle Keith Milburn & his wife Ella. Keith was a keen fisherman and whilst Ella managed the day-to-day running of the Hotel, Keith was busy with the family business in Keswick, Milburn & Sons, on Borrowdale Road. Keith was also sergeant for the local Home Guard, The Lorton Platoon, and meetings took place throughout WWII at Scale Hill (read on for more!)

Ella & Keith Milburn, with Ella’s sister and Storm the dog, 1930s

Keith Milburn weighing his catch

An old Hotel brochure from the Milburn era

Scale Hill in the 1960s, with Judith Benn on the Horses and Margaret Jackson

Scale Hill with mighty Grasmoor towering behind her

Scale Hill in WWII

In 1940 The Lorton Platoon was part of the 4th Battalion E group under the command of Colonel GT Pocklington-Senhouse of Maryport, and affiliated to the Border Regiment. Initially the Lorton platoon comprised 8-10 men led by Mr Gamlin of High Lorton as commander, with a WWI veteran, Jimmy Nicholson, as second in command. Other war veterans in the group included Tom Lister and Joe Walker, who at this time was a farm hand at Bridge End Farm.

On 22nd July 1940, following a suggestion from Churchill, the name of the Local Defence Volunteers was changed to The Home Guard. Around this time men from the Loweswater and Buttermere areas joined the Lorton platoon and were organising joint training exercises with Border Regiment troops and the Portinscale and Ullock Home Guard.

Dick Bell was the platoon wireless operator and he cycled to Cockermouth one night each week to learn Morse Code. On a regular basis, two men were stationed each night at Crummock Water in a corrugated hut situated between the sluice and Park beck incase an enemy seaplane tried to land on the lake. Two men were also stationed on the Howe above Scale Hill, which gave a good view point over the whole valley. There were also visits to the rifle range at Winscales but the shooting practice was carried out across the Hows at Scale Hill.

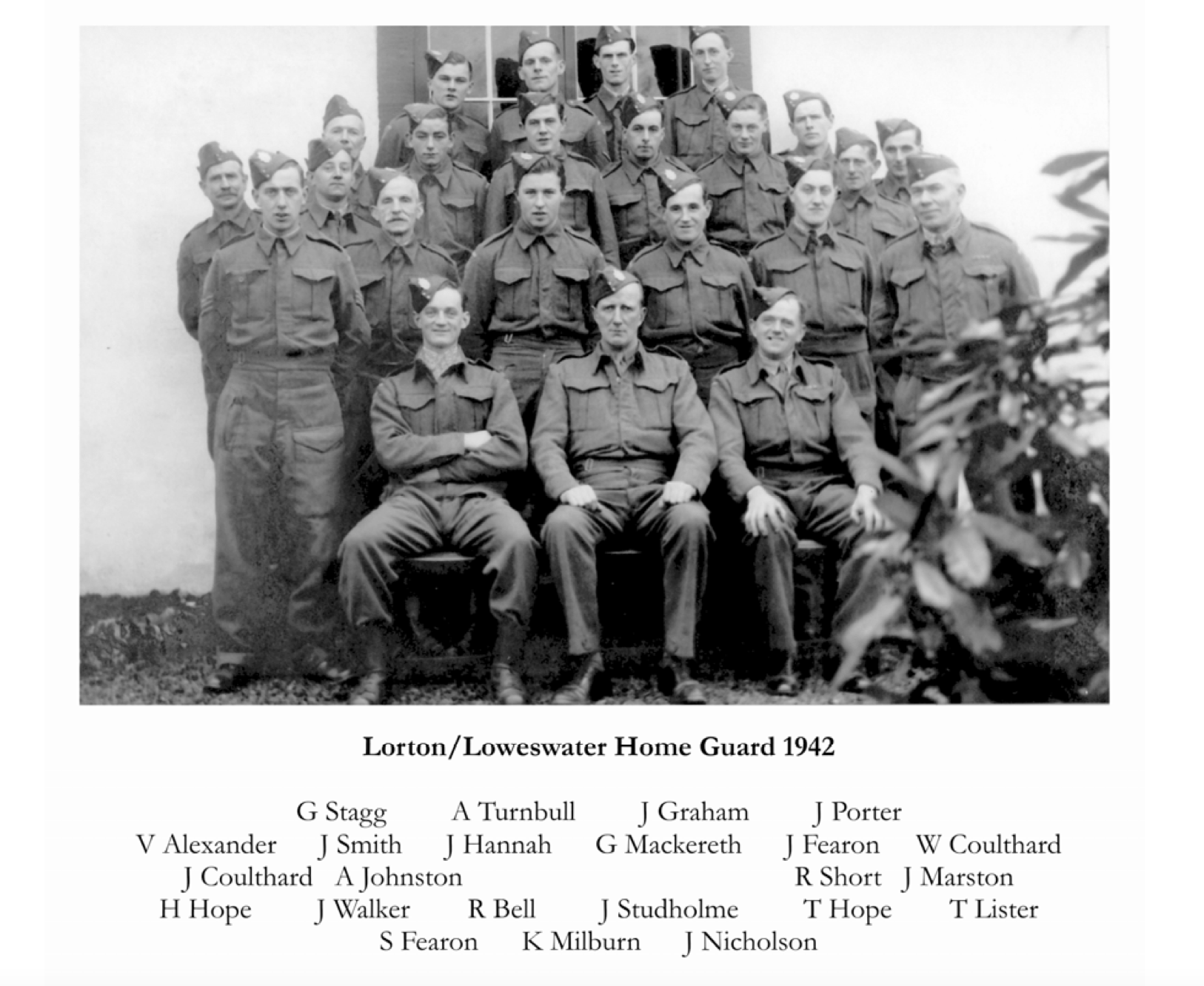

In 1941 conscription was introduced in some areas to keep the Home Guard up to strength and members were required to attend parades twice per week, on Wednesday night and Saturday mornings. They paraded and held rifle drill in the Lorton School Yard or at Scale Hill Hotel. Keith Milburn (front centre) a sergeant at the time, was the owner of Scale Hill Hotel. Here are the members of the Home Guard in 1942, sat outside the Dining Room on the Terrace at Scale Hill Hotel.

Notable Visitors During the Milburn Years

Joyce Grenfell & Viola Tunnard

William Arthur Poucher

Viola Tunnard

The pianist Viola Tunnard is one of the great forgotten musicians of last century. Accompanist and mentor for some of the great singers such as Dame Janet Baker, Peter Pears and Robert Tear, Tunnard was a member of Benjamin Britten's English Opera Group, and toured with the singer and comedienne Joyce Grenfell during WWII. To celebrate the centenary of her birth she's remembered by the conductor Steuart Bedford, pianist Roger Vignoles and through Grenfell's letters.

Listen to BBC Radio 3’s programme about Viola here at 17.50

William Arthur Poucher

Better known as Walter, a nickname he acquired during his Army service, W. A. Poucher (1891-1988) was one of the leading British mountain photographers and guide book writers during and following World War II. He personally explored and photographed all the routes he describes in his famous mountain guides, so that users can be assured of correct directions. He was an accomplished and skilled photographer. He joined the Royal Photographic Society in 1940 and was awarded Honorary Fellowship in 1975.

Poucher was a research chemist by profession, who specialised on the chemistry of perfumes, cosmetics and soaps for Yardley. His 1923 textbook Perfumes, Cosmetics and Soaps has been revised and reprinted over the years and is now in its 10th edition. He was frequently given leave of absence by Yardley for part of the year to pursue his mountain photography.

Joyce Grenfell

Joyce was a regular visitor at Scale Hill, the extract below is from her book ‘In Pleasant Places’

The ‘certain small valley in Cumberland’ mentioned in ‘My Kind of Magic’ has been important to Reggie and me for over twenty years. I won’t give its name, because already that part of north-west England is overrun with caravans cars, campers and coaches. In Summer the hills are not only bright with heath and small flowers, but they also dazzle the eye with hot orange and aggressive royal blue canvas tents and lean-tos. Selfishly I am glad the secret valley road is so narrow that coaches are banned from using it. They can get everywhere else in the district, but so far, it has not proved practical to widen this road. Once a day a local bus takes valley schoolchildren and shoppers to and from the nearest towns, but monster coaches on ‘Mystery Tours’ are forbidden entry.

The first time I saw the valley I had an unexpected homecoming feeling about it. Viola Tunnard and I were booked to do two weeks of concerts in music clubs in Lancashire and West Cumberland. We planned the route together, and decided to look for an hotel that would be a base for the second week of the tour, when all the engagements were within twenty miles of each other. We were sure there must be a central point in that beautiful hill country from which we could work; but neither of us had been to Cumberland, and nobody could advise us. I got out a three-inch relief map that showed very few villages and plenty of brown shading; that meant hills. My hotel guide had pages of coloured pictures advertising hotels in the specified area. None of them looked inviting, but at the back of the book were unillustrated entries, and among them we found a short paragraph describing a three-hundred-year-old coaching inn – with a reputation for hospitality, comfort, and excellent home cooking – set in a peaceful stretch of valley, with mountain views. There was fishing available, and the nearest rail-head (long disappeared) and market town were eight miles away. We looked at the map. Between two small hamlets, just above a winding river, was the word ‘INN’. It was situated at exactly the right place for our needs – none of the concert halls was more than twenty miles away.

I telephoned from London to ask for two single rooms, confirmed the booking by letter, and on a cloudless, cold April day in 1958 Viola and I left the town where we had played the night before and drove up a steep pas that came down the other side of a wooded mountain, to grassy slopes and the open view of the shallow valley ahead of us. We stopped the car. Creamy bird-cherry foamed in the hedges, and a few early bluebells were coming up through new bracken on the hillside. I turned off the engine. We could hear cuckoos calling, lambs bleating and waters, in the little beck some way below us, running over rocks. Splendour!

It was then that I said ‘This is it!’ not entirely knowing what I meant, but feeling confident in my words, as I said them. Viola agreed it was a good place, and later she told me she had had the same intuitive tingle of a right arrival as we first looked down on the valley that was to mean so much to me, and later to Reggie. Viola didn’t return there as regularly as we did, but she shared our feeling for the place, and whenever she and I did concerts together in that part of the country we always stayed there.

We drove on through small fields between stone walls. I was glad to be away from towns and out of the touristy part of the Lake District. Even inside the car the air smelt fresh and sweet. Around a corner, up a rise, we came upon the long, low, whitewashed two-storey hotel, sitting in a garden filled with azeleas, tulips, forget-me-nots, wall flowers and polyanthus. It accommodated about twenty-four guests. The visitors’ book was full of bishops; their name and the names of many of the other guests, recurred year after year.

The Milburns, who owned the hotel, greeted us. Keith, the extrovert, a great fisherman and born host, came out from behind the tiny bar, too small for more than three visitors at a time. Drinks were handed through a hatch and consumed around a fire in the cosy entrance hall. Ella, reserved and shyer, emerged from the kitchen where she supervised all the meals and cooked a good any special dishes herself. Keith was tall and good-looking; she was small and trim in a dark red twin-set and a neat tweed skirt. Her hair was braided around her head. Both were then in their fifties. Robert Branthwaite, then the general helper and waiter, fetched the bags. Our small bedrooms faced the view of High Fell, across an open valley – it gives a feeling of shelter and space – and to our left widening meadows spread to further hills and woods. I opened my window and heard a curlew crying. For luncheon there was a perfectly cooked cold roast duckling, followed by apple crumble with a generous sugary crust and thick cream. Ella and Mrs Robinson, who helped her, produced the kind of menus you don’t often meet in small country hotels, all of them delicious.

We had a good week. Viola and I spent our mornings exploring the woods; we found the lakes and walked for miles. One day she went fishing and I did some sketching. Every evening Ella gave us an early high tea in the empty dining-room before we went off to work. All the small tables in there had been found by the Milburns at local auctions and no two were alike. As she got less shy of us Ella opened up, and when she had given us our meal she came and sat at our table. At first, I think, she was a little suspicious of us. We were an unknown quantity – Viola a musician and I a ‘theatrical’ – but she was curious to know about our lives and the jobs we did, and we made friends. We left the hotel each evening at about six o’clock to drive across country to the various halls along the coast.

In spring and summer, in this part of England, the daylight lasts until eleven at night. Driving back to the hotel, all that week of clear cool weather, I stopped the car each night at the same red telephone-box and reversed the charge for a call to Reggie, in London, to report on the day’s doings. The telephone box, one of Sir Edwin Lutyens’s beautifully proportioned designs, was the only man-made object in a single-street village of mean little terraced houses on the edge of the moors, that stood up to the scenery. I enthused about the concerts – given to friendly audiences – and said: ‘We must come here together.’ It was all enjoyable – the countryside, the hotel, the food, the Milburns and the valley.

Ever since that first visit to a place, chosen more or less with a pin twenty-one years ago, Reggie and I have been back at least once a year, usually in May. Once we went in June in a year of spectacular wild roses that festooned the hedges like curtains, and sometimes we have made two visits, the second in October – burnished bracken, blackberries and mushrooms.

Joyce Grenfell

The front cover of Grenfell’s book In Pleasant Places, the photograph is taken in the garden at Scale Hill, looking towards Melbreak & Loweswater

The Thompson Era 1966-Present Day

Keith and Ella Milburn ran the hotel successfully until 1966, when it was purchased from them by their nephew, Michael Thompson and his wife Sheila. Michael had grown up in Keswick, surrounded by Milburns and Thompsons. Instead of going into the family Land Agency business, Edwin Thompson, Michael went Dairy Farming in Lancashire after he had finished his National Service.

Whilst farming, he met Sheila, and after many years on the Farm they moved to Loweswater in 1966 to run Scale Hill Hotel. They raised their two daughters, Heather and Hazel in Loweswater, and both of them were involved in the business during the 1980s and 1990s.

Neville Goodfellow, from Keswick being closely watched by PC John Turnbull who used to stop in at Scale Hill to use our telephone to check in to the local police station!

Scale Hill, Winter, 1990s

Pony Rides at Scale Hill

A Scale Hill Postcard, 1960s

Heather and Hazel Thompson on the Grassy Knoll at Scale Hill, 1960s

Heather Thompson, Buttermere Church

Soon after, Hazel moved to New House Farm in Lorton, which was a Lakeland Farm before she transformed it into a Wedding Venue. Heather moved to London and worked for the Amateur Athletic Association, or “the three A’s” for some time until returning to the Valley to raise her three children, Megan, Derwent and Hayden and take over the family business at Scale Hill.

In 1990 the Hotel was closed by Michael and Sheila and parts of the Coach House and other buildings were transformed into Cottages. Involved in the business since the 80’s, Heather and her family moved to Scale Hill in 2002 and she has been successfully running the business ever since, as well as doing plenty of detective work with regards to the history of this unique and well-loved building.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, parts of the Scale Hill were redecorated and have since been transformed. New life has been breathed into the building, restoring parts of the Hotel whilst preserving its unique and long history.

Scale Hill is still a family business, run by Heather Thompson and her grown-up children Megan, Derwent and Hayden who are the fourth generation of the family to be involved in the business. In many ways, Scale Hill has always been an ordinary home with a rich history like many other houses - it is the visitors who have brought joy and life to this building, and in doing so they have made Scale Hill a special place for those who stay, for those who reminisce, and for those still yet to discover her.